Don’t Screw it up.

It’s the most common piece of advice Mike Bloomberg gives employees at his company.

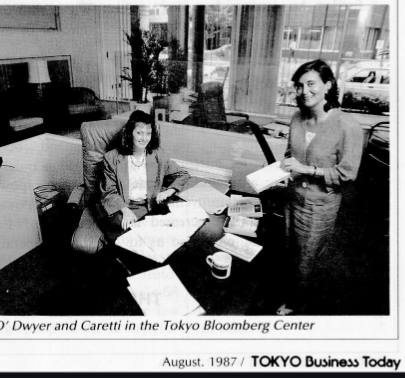

A friend of mine, Ellen O’Dwyer, was on the receiving end at the highest stakes moment of her career.

It was 1987. Mike had decided to dispatch Ellen and a colleague to co-open an office in Tokyo.

Ellen was just 24. She had never been to Japan. To say she was anxious would be an understatement.

Ellen spent a few weeks getting organized and when the day came to leave, she stopped by Mike’s desk to say goodbye. She was looking for some parting advice.

When she approached, he was on the phone. She waited uncomfortably. Eventually, he put his hand to the mouthpiece and asked her what she needed.

“I’m leaving for Tokyo,” she said. “Is there anything you need to tell me before I go?”

He looked at her like the answer was obvious.

He smiled and said: “Don’t screw it up.” Then turned back to his call.

Don’t screw it up — along with a variation that included a swear word — was a frequent and favorite admonition to employees in the early days. I heard it scores of times while I worked at the company.

The advice was always delivered with a playful, ironic tone. It was not cold or callous. It was meant to be lighthearted and over time became a signature line.

Mike would use it as punctuation to meetings after a decision had been made or, as he did with Ellen, to signal that there was really nothing more to say. It was time for action.

It’s out of step with today’s let-me-know-if-you-need-my-help style of leadership, which sounds supportive, but actually suggests you can’t really handle it.

By contrast, “Don’t screw it up” implies the opposite to me. It says: “You know what needs to be done. Don’t overthink it. Don’t get in your own way. Just do it.”

Ellen started at Bloomberg as an intern in college when there were fewer than 20 employees.

She joined full time in 1985 to work on client services and sales. Mike demanded frequent reports on usage, worried (then as now) that clients weren’t using all the applications. It was high energy. A bell was rung for each sale.

Ellen said that by necessity she learned every aspect of operations. “I could reset the mainframes. I could give demos and run reports. I knew all the parts of the business.”

That may explain why Mike disregarded the advice of others to send a man to open the first office in Asia and instead asked two women, Ellen and Paula Caretti.

“Can I sleep on it?” Ellen remembers asking.

Mike suggested she take a five-minute nap in the conference room and let him know.

She took the job and left for Japan a few weeks later.

She didn’t screw it up.

(Part of a series of management lessons learned from three decades at Bloomberg)